Discussions with FIG Members Judith Christensen and Amanda Saint Claire

Judith Christensen

We All Forget a Word Now and Then, Dictionaries, paper, ink, wax

My path to artist’s books was roundabout rather than direct. While pursuing my career as an art critic, I happened upon the field of book arts, which, with its fusion of text and narrative with structure and image, intrigued me.

As I was reviewing every artists’ books exhibition I could find in Southern California, I felt constrained by the scarcity of professional resources, particularly in terms of historical context. To help fill that gap, I asked to audit a class at UC San Diego taught by Ian Tyson, a visiting book artist from Europe who, as one gallery director told me, “Has been around forever.” The only requirement he placed on me was that I had to participate by making a book. I thought, “How hard can that be?” Harder, I learned, than I imagined and more stimulating as well. It took me five years to finish that first book.

The Place We Return to is Home, Paper, ink, wax, foam board, wood

Receptacles for Memories that Can’t Possibly be True, Classic Crest Cover-Millstone, ink, wax

I transitioned gradually from writer to artist. At the beginning, gaps in my art-making were measured in years, but I always returned, spreading out on the dining room table for a few hours before clearing space for eating. During that time, my involvement with San Diego Book Arts and the artists I met through the organization sustained me. If I wasn’t making books at that time, at least I was engaged with others who were. We shared ideas, processes, exhibition opportunities, successes and failures. We went on field trips to the Getty Special Collections; we got together to make paper; we taught classes at schools and libraries; and, through the Edible Book Teas, I established a relationship with Lynda Claassen, Director of the UC San Diego Special Collections, where several of my artist’s books are nowhoused.

One form I gravitate towards is the house. I view the narrative of a life as rich and boundless. Every minor detail of an everyday life matters. A house has a presence and a significance that goes beyond the copper pipes, studs, insulation, and roofing. It provides the framework in which we converse, eat, sleep, procreate, and, for some, die. It serves as the container for the objects we collect, store, and arrange. It is also the repository of our memories, the life we spend there. I like Gaston Bachelard’s term, “inhabited geometry,” to characterize this intermingling.

As the scale and scope of my work progressed, I became involved with two other artists’ organizations, Allied Craftsmen of San Diego and Feminist Image Group (FIG), both of whom actively pursue exhibition opportunities. When the call went out for artwork for “Make Yourself at Home” at the San Diego International Airport, I had not just one or two pieces, but a complete body of work for the curator to choose from. This summer I will install several artists’ books and over one hundred miniature houses to be on view for the next year at the airport.

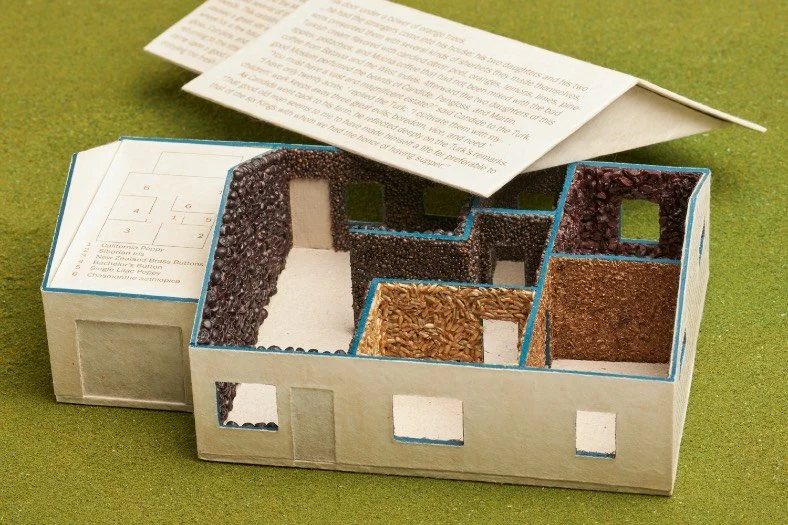

We Color in the Outlines of our Memories with our Beliefs, Paper, seeds, paint, fine cinders, green blend turf

Contract for Building a House, Handmade paper, Kozo-Shi light paper, thread

“Tis well said,” replied Candide, “but we must cultivate our gardens”, Book board, handmade paper, paint, Kozo She, seeds, wax, green blend turf

Interview with Amanda Saint Claire

How did you become interested in working with people on the Spectrum?

I was initially drawn to serving all adults to help them tap into their creativity as a means of coping with health opportunities and working with artists struggling with perfectionism. Not all artists allow themselves to explore the fullest potential of their creativity. It’s still my intention to serve a wide range of individuals, but I do find I have a calling to provide services to adults with intellectual, physical, and emotional challenges.

When did you start teaching art to people with Autism?

I first started with adults with intellectual disabilities in Oceanside at Studio Ace. At that time I was studying to become an expressive arts therapist. I’ve since switched my educational goals to be an expressive arts coach and educator. I enjoyed the experience and applied for a small grant that paired local artists with artists on the spectrum for a program called Radical Inclusion. That was when I was paired with an artist on the autism spectrum. That led to other opportunities, including my work as a paid mentor in the Self Determination program and these continue to expand. A Veteran myself, I recently taught a zoom class in art journaling to veterans through the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco. Some of the participants had PTSD and TBI, some were artists, and some not, but luckily I was able to make the experience accessible to everyone. This is what I love about all the arts. They unite us and create community, and community saves lives.

What is your understanding of Autism, then and now?

Before I started working with individuals on the spectrum I really didn’t have any exposure to anyone with Autism. I’d grown up with deaf grandparents but that was really the extent of my day to day life with someone with a disability. Working at Studio Ace as a volunteer with adults with a variety of intellectual disabilities, was my first introduction to individuals with different capacities. What I noticed right away was that every individual is very different. There’s a saying in the community that if you know one person with Autism, you know one person with Autism. It’s not a one-size fits all community, except for the anxiety. The anxiety is pretty common across the board there. And that would be the one thing that I would say I became aware of: how to manage those anxieties as they manifest in different individuals in order to get them through the art process.

I think art can bring up anxieties in everyone. In neuro-typical people, if it’s something outside their comfort zone, it’s going to bring up anxiety. I know for myself, there are certain types of things I do in my studio. I have to navigate my own anxieties to get there. So, having had that experience within my own art practice, I think it gave me some insight as to how they must be feeling, although magnified a lot. And what I learned with working my students in my studio so far is that each person’s anxiety presents differently.

With my first student, Jack, I had to give him a.lot of space. He would get very physical when he got anxious, so I had to give him a lot of space to wander through, and work through, and talk through the process. And just give him a lot of time to come to what I was asking him to do. Sometimes it took him an hour to get to a space; he wanted to do it, but the anxiety was prohibiting him. My job is just to wait, create space, not to keep interfering, just kind of sit back and watch.

With my other student, Katie, her anxiety presents in a different way, and I’ve learned how to approach her. It’s a different sort of process. Again, it’s the same thing. I just have to allow them to move through the process even if it gets uncomfortable, without interfering. I’m there in a supportive role, and I try to not react. I try to make myself as vacant as possible, if that makes sense, spacious inside. I don’t try to project anything. I don’t take anything personally. I try to make myself - and I can’t always do it and sometimes I feel like I’m not getting it right - but I try to create that space to allow whatever anxiety they’re projecting out, I can just take it in as a sponge and not deflect it back at them. And eventually, usually, we can get through it and the creative process happens. I was sort of surprised at how it came to me. It wasn’t that difficult for me, at least that’s what was reflected back to me by others.

Are you prompting, guiding, reminding, talking at all when you’re creating that space?

It depends. With Jack, he didn’t like it if I talked. He would ask me to be quiet, and would tell me that I talked too much, so with him, I’d have to mind my own business. He knew what was expected of him. He wanted to participate but I had to just wait for him to sit down and start doing his thing. With Katie, she gets a bit more emotional. She’s not physically activated during that process. It’s more of an emotional response, so with her, it’s more talking. It’s more supportive, like “It’s ok, it’s ok to be upset.” So with her it’s more talking her through it.

What have you learned about the creative process in this work?

I’ve learned that you have to be very creative to do this work because you have to find creative solutions to road blocks constantly, if someone comes in and they’ve had an anxious morning, or things happened at home or in another space. If I pick up Katie and she’s already very anxious, then we have to work through that. There have been some periods of time where we’ve had to regress. One activity that really calms her down is rolling, rolling the walls. If I notice that it’s been more than one day and the anxiety is still really really high, I’ll suggest to her that we paint her studio. We’ll take a couple of hours or sometimes a couple of meeting times and we’ll just repaint the studio. The rolling activity, the methodical motion, is very soothing for her. So it’s reading the cues, not always having an outcome or an agenda, but meeting the person where they are. I’ve learned that sometimes we have a deadline for a show but we’ll have to take that time, step back, recalibrate her nervous system. It’s affected my own art practice I’m working with acrylic more now, mixed media, because it’s more immediate and I can move stuff around. I think it’s just expanding my own sensitivities as I work with media since I have to be more creative rather than getting upset and saying I can’t do this any more, I say, well, do this, try this.

I’ve been working with a young man who’s 16 or 17. I don’t see Ben that often since he lives further away but Ben’s in a wheelchair and he’s legally blind and really only has the ability to hold a tool in one of his hands. He’s got a lot of physical impairments and when I work with Ben, it’s a matter again of creating a lot of space, time and patience. I’ll come in with a lot of ideas of things we could do and we’ll probably only get to 25% of them if we’re lucky because for Ben, he’ll get fixated on looking at a color or the tapping noise. His sense of sound is very highly developed because he can’t see that well. Sometimes it’s the beating of a spatula on a stretched canvas that’s basically a drum. Sometimes it’s the beating of a drum and the splashing of the neon paint. Sometimes we’ll just do that for an hour. And he’ll be mesmerized, and then on the way home, his mom will tell me he’s just lighting up his keyboard with ideas of things he wants to do.

People will ask me, how do you know what to do for each individual? I don’t do a lot of advance prep. i’ll gather things that I think might be of interest to an individual and then I’ll just kind of see what arises and take my cues from them. I don’t have a set agenda. I’m like that when I work with

There are so many different abilities and strengths among people on the spectrum.

Sometimes I’ll approach people through an entirely different artistic form. With the adults on the spectrum, I find they’re very drawn to music. I have a guitar at my studio and two different kinds of drums. Some days we’ll drum for half an hour before we ever pick up a paint brush. That’s true with working with neuro-typical individuals too. Sometimes inviting movement or working with poetry is a way of circumventing the anxiety of working in visual art. If you approach it through a different medium, you transfer over. That’s what it feels like in your body, that’s what it sounds like, now what would it look like? Taking it across, and the back door to anxiety as well. The right brain doesn’t have a way to express itself verbally. It stores images, it stores memories, it stores trauma sometimes; there’s pre-verbal traumas in there. The body has a lot of memory that is cut off from the head, if you will, and some of us live mostly in our heads, so it’s getting the body involved. I’m interested in it because it’s my own healing journey. Painting, and painting really large allows everything to flow.

FIG News - to help us stay connected!

If you’d like anything FIG-related included in the Newsletter, feel free to email the newsletter email at OurFigNews@gmail.com and kitaaboe@gmail.com, and the info will be included in the next edition. Send any questions about FIG News to those emails too. Kirsten Aaboe will reply.